- Mindsailors

- Blog

- sustainabledesign

- A New Era of Materials in Product Engineering

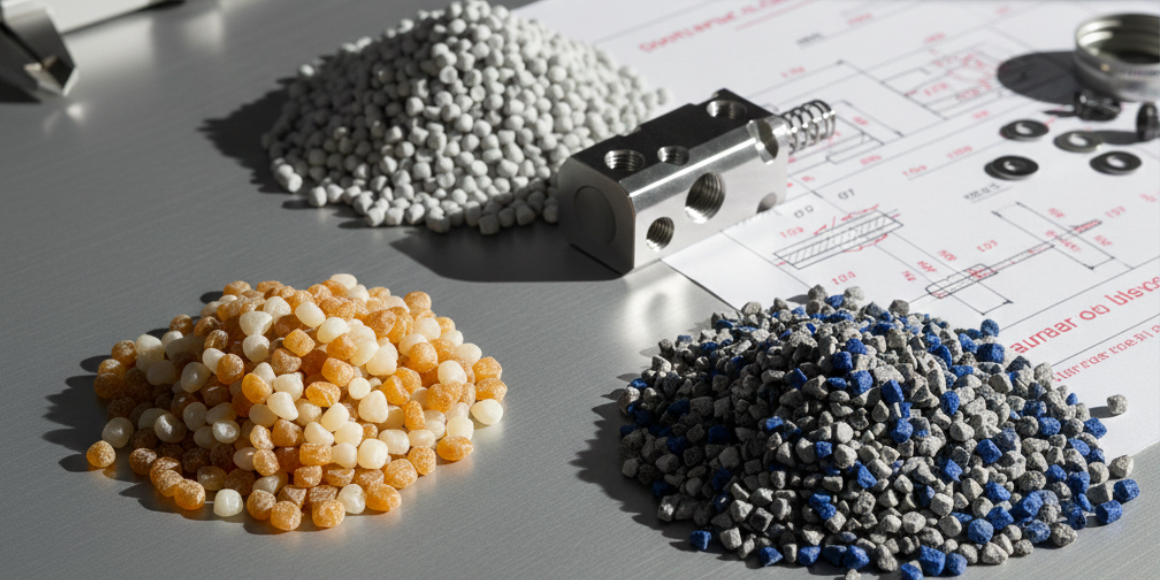

Faced with the growing challenges of environmental degradation and the pressures of a circular economy, product design engineers are facing a new reality. Traditional petrochemical materials, which dominated the industry for decades, are gradually being replaced by advanced alternatives: bioplastics, recycled materials, and smart materials. These innovative material solutions open up new possibilities in product design, but they also pose significant technological and economic challenges for designers and production engineers. Understanding their properties, costs, availability, and application potential is crucial to creating future products that are both efficient and sustainable.

Bioplastics – From Theory to Practical Applications

The bioplastics market is experiencing dynamic growth, although data requires careful interpretation. Global bioplastics production capacity was 2.47 million tons in 2024. Estimates for 2025 point to 2.31 million tons. This is not a decrease, but a revision of estimates resulting from more precise reporting and the exclusion of so-called "mass-balanced capacities" from the models, which do not meet the criteria for pure bioplastics. It is important to note that in 2025, the industry 's capacity utilization rate was 72%, which translated into 1.67 million tons of actual production. Forecasts until 2030 remain optimistic, with an expected increase to 4.69 million tons, mainly due to the expansion of bio-PE and bio-PP production in Europe.

Bioplastics are not a single, uniform category of materials. There is a wide spectrum of types, each with properties tailored to specific applications. Polylactide (PLA), derived from renewable resources such as corn and sugarcane, has found use in both packaging and more advanced applications. Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) exhibit properties similar to conventional plastics while being biodegradable under natural conditions. Polybutylene succinate (PBS) and its blends with other biobased polymers offer improved mechanical properties compared to pure PLA.

.png)

From a Design for Manufacturing (DFM) perspective, working with bioplastics requires advanced knowledge of their thermal and mechanical behavior. Although PLA is a popular choice, it is sensitive to high temperatures and mechanical stresses. This means engineers must carefully design injection processes, taking into account lower mold temperatures and sometimes longer cooling times. The Design for Manufacturing and Assembly (DFMA) methodology allows for optimization of the PLA production process, reducing material waste and labor time spent on final assembly.

Specific commercial examples demonstrate the practical applications of bioplastics. Coca-Cola has launched a 100% Plant-Based Bottle and is also testing PEF (polyethylene furanoate) bottles. Procter & Gamble uses bio-PE for cosmetics packaging, as do L'Oréal and Unilever as part of the Ellen MacArthur Foundation's commitments. In Australia, Plantic Technologies produces corn-based bioplastic packaging for the food industry. The packaging segment dominates the bioplastics market, accounting for 45% of global production capacity, but there is growing interest in using bioplastics in durable items, products requiring higher performance parameters, and even medical devices.

Recycled Materials – Designing with Existing Waste Streams

Design from Recycling (DFR) represents a paradigm shift in sustainability. Unlike traditional "Design for Recycling," which focuses on recyclability at the end of a product's life, the Design from Recycling methodology starts with existing waste streams and creates new products for them.

However, using recycled materials in production presents designers with practical challenges. The main problem is the variability of material properties. While virgin materials have well-defined and consistent properties from batch to batch, recycled materials exhibit high variability in chemical composition, thermal characteristics, and rheological behavior. This is due to the heterogeneous origin of the waste: they may contain mixtures of different polymers, residual additives, or contaminants.

Material costs are another critical factor. Producing one ton of virgin plastic costs on average €800–1,200, generating 1.7–3.5 tons of CO₂. The mechanical recycling process costs €400–600 per ton, but recycled pellets (R-PET, R-PP, R-HDPE) cost €700–1,000 per ton. Paradoxically, in Europe in February 2025, rPET was $750–800 more expensive than virgin PET, due to shortages of high-quality raw materials, sorting and purification costs, and low oil prices that keep virgin plastic production costs low. This gap in the circular economy poses a major challenge to commercialization.

For DFM engineers, this variability and cost structure create narrow process windows. When injecting recycled polymers, differences in viscosity, moisture content, or degradation rate can lead to:

- Inhomogeneities in the mold filling – air pockets, irregular joint lines or incomplete filling may occur

- Dimensional and aesthetic instability – differences in packaging and cooling affect material shrinkage, leading to warping and surface irregularities

- Narrowed process window – the system becomes more sensitive to small changes, requiring more precise parameter control

Despite these challenges, closed-loop injection molding with sensors (closed-loop injection molding with adaptive parameter control) is showing promising results. This technology measures the actual behavior of the material inside the mold and adaptively adjusts parameters to compensate for batch-to-batch variations.

For prototyping and small-scale production runs, thermoforming is proving to be an attractive alternative to injection molding. Although less precise, the thermoforming process offers lower tooling costs and a faster time-to-production, making it ideal for large-scale products with a low component count.

The "Design from Recycling" project developed at the University of Antwerp provided practical guidelines for engineers designing products from recycled polymers. The methodology consists of a six-step process: technical characterization of the material stream, assessment of the material's unique sensory properties, formulation of a vision for the material experience, idea generation, development of design guidelines, and final prototyping.

Smart Materials – New Dimensions of Functional Design

Smart materials represent the most transformative category. The smart materials market is estimated at $78.27 billion in 2024 and is expected to reach $169.62 billion by 2034. These materials, which actively respond to environmental factors - such as temperature, electric fields, mechanical stress, or magnetic fields - open up entirely new possibilities in product design.

However, the challenges of commercialization are significant. Integrating smart materials requires a complete redesign of the supply chain. For many companies, it's not just about switching suppliers but also building new partnerships with specialized manufacturers, often requiring collaboration with research institutes. Furthermore, smart materials require significant infrastructure investments: sensors, control systems, and simulation software – which poses a barrier to entry for small and medium-sized enterprises.

Piezoelectric materials accounted for the largest share of the smart materials market in 2024, generating electricity in response to mechanical stress. They are used in sensors, medical devices, and vibration-reduction systems. Their reusability and precisely controlled response make them particularly valuable in applications mandated by regulations and safety standards.

Shape memory materials (SMAs) demonstrate the ability to return to their original shape after exposure to heat or electrical current. While SMAs (Shape Memory Alloys) demonstrate tremendous strength and high energy efficiency, they impose significant design complexities. The key challenge is that smart materials must be integrated very early in the design process, rather than added later to existing designs based on conventional technologies.

.png)

An innovative direction is 4D printing - an extension of 3D printing in which components can change shape or properties in response to external stimuli. The MIT Self-Assembly Lab, in collaboration with Stratasys and Autodesk, has developed 4D printing technology using Connex multi-material printers. The lab's programmable materials include self-transforming carbon fibers, printed wood structures, textile fibers, and rubber-plastic composites, which offer programmable actuation, sensing, and material transformation. The goal is true material robotics - "robots without robots," where the material itself, devoid of traditional electronics and motors, possesses built-in adaptability and movement capabilities.

In November 2024, researchers at the University of Colorado presented groundbreaking work on multifunctional composites that can change shape through precise fiber orientation. The MIT Self-Assembly Lab is exploring bio-inspired materials capable of self-repair (self-healing), as well as Rapid Liquid Print technology, which prints large, stretchable products such as interior furnishings and prosthetics, and Liquid Metal Printing, which creates furniture from molten aluminum in minutes.

The reactive structural materials (smart structural materials) segment is projected to grow the fastest in the coming decade. Designed to enhance structural strength, these materials are finding applications in the construction and automotive sectors, where self-healing polymers can extend product life and reduce maintenance costs.

The Future Lies in a Multidisciplinary Approach

The practical application of all three categories of materials requires a much broader knowledge base from designers and production engineers. The commercialization of bioplastics is driven by increasing European regulations, such as the Circular Economy Action Plan and the EU Green Deal. For recycled materials, mastery of characterization and quality control techniques is crucial to managing process variability. Smart materials, on the other hand, require advanced design tools and experience with multidisciplinary teams - traditional engineering knowledge is often insufficient.

Institutions like MIT, Dassault Systèmes, and Autodesk are investing in simulation tools that enable designers to predict material behavior under various conditions. Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning technologies are accelerating the material selection process by analyzing vast data sets and identifying the best materials for specific applications.

The transformation taking place isn't just a change in materials, but a shift in the entire philosophy of product design. Circular engineering (sustainable design) no longer considers product launch as an endpoint, but rather plans for a second life for it - through repair, remanufacturing, or recycling. This holistic perspective is changing the way engineers approach every phase of product development, from concept to production and end-of-life.

A New Era of Materials in Product Engineering

Schedule an initial talk and get to know us better! You already have a basic brief? Send it over so we can have a more productive first meeting!

a meeting