- Mindsailors

- Blog

- industrialdesign

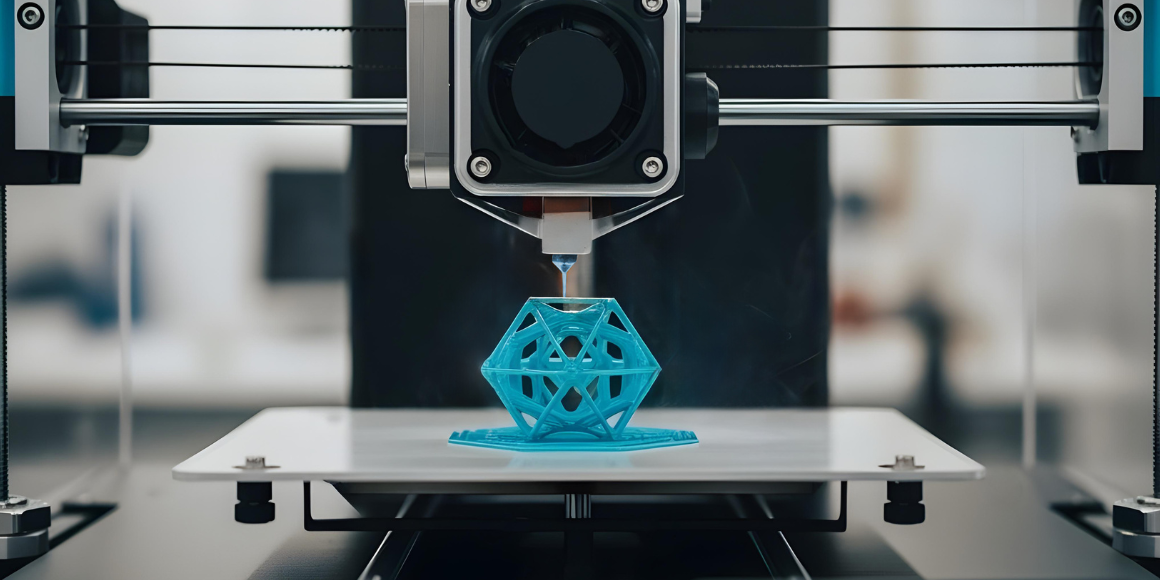

- Rapid Prototyping Using 3D Printers: From Concept to Prototype in 24 Hours

The slowest part of many product development programs is still physical validation. A CAD model can be updated in minutes, but traditional machining or outsourced prototyping often stretches a single iteration into one or two weeks. Rapid prototyping with modern 3D printing compresses that loop to roughly 24 hours from design decision to functional part, giving engineering teams a structural speed advantage rather than a marginal efficiency gain.

Why 24‑Hour Prototyping Matters

In a typical legacy workflow, a design flaw discovered on Friday might not be physically validated until the following week, after external shops quote, program, machine, and ship a prototype. Each iteration consumes calendar time, budget, and management attention, which in turn discourages experimentation and encourages compromise.

With an in‑house, tightly disciplined additive workflow, design changes made in the morning can be validated the next afternoon. A product that once required 5–6 two‑week cycles can realistically move through the same number of iterations in 10–12 days rather than 10–12 weeks.

Elite development teams can achieve complete validation cycles within 24 hours, while traditional prototyping workflows typically require 7–14 days per iteration when using machined or outsourced prototypes. For teams competing on performance, customization, and time‑to‑market, that gap becomes a core strategic differentiator rather than a marginal process tweak.

The Technology Landscape: SLA, FDM, SLS

Different 3D printing processes are not interchangeable; each brings specific strengths, limitations, and cost structures that must be understood at the design stage.

Stereolithography (SLA)

SLA and its masked variants (MSLA) use light to cure liquid resin layer by layer, producing parts with high resolution and smooth surfaces suitable for enclosures, ergonomic models, and tight‑tolerance features. Current generation machines can complete small assemblies in a few hours, with build‑time scaling primarily with vertical height rather than the number of parts in the chamber.

Engineering‑grade resin portfolios now cover rigid ABS‑like materials, high‑temperature blends, flexible elastomers, and glass‑ or ceramic‑filled systems for stiff components, which allows a single printer platform to support multiple validation needs.

The tradeoffs are support structures that require post‑processing, sensitivity to exposure and curing profiles, and long‑term creep and aging behavior that diverge from traditional thermoplastics.

Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM)

FDM extrudes thermoplastic filament such as PLA, ABS, PETG, or engineering grades like nylon and polycarbonate through a heated nozzle. Desktop systems are widely accessible and cost‑effective for concept models, jigs, and non‑critical fixtures. Material costs are low, and many teams already own at least one FDM printer.

However, FDM's mechanical behavior is strongly anisotropic; parts are weakest along the layer interface, and visual quality often depends heavily on operator tuning and post‑processing. Complex geometries with overhangs, thin walls, or fine detail can lead to long print times - 10‑hour builds for moderately complex parts are common - and labor‑intensive support removal. For functional prototypes where geometry, tolerances, and surfaces mirror production, FDM is often more appropriate as a supplementary capability than the primary validation tool.

.png)

Selective Laser Sintering (SLS)

SLS uses a laser to fuse layers of polymer powder - commonly nylon 12 or similar engineering materials - while unfused powder acts as a natural support, eliminating traditional support structures. This enables complex internal channels, undercuts, and nested assemblies without the support removal burden found in FDM and SLA.

Mechanically, SLS nylon parts can achieve tensile strengths of 45–50 MPa - approximately 80–90% of injection‑molded PA12 - when process parameters, powder refresh ratios, and post‑processing are well controlled, making them suitable for snap‑fits, load‑bearing brackets, and functional fixtures. The main drawbacks are higher capital expenditure, powder handling infrastructure, and batch‑oriented build cycles that favor overnight packing of the build volume rather than one‑off prints.

.png)

The 24‑Hour Workflow: Design, Print, Validate, Iterate

A true 24‑hour cycle is less about printer speed and more about disciplined orchestration of design, preparation, printing, and post‑processing.

1. Morning: Design and Design for Additive Manufacturing

The cycle starts in CAD with a clearly defined design question: a new snap‑fit geometry, revised mounting boss, or modified housing interface. Rather than designing generically and hoping the printer will cope, the team applies Design for Additive Manufacturing (DfAM) principles from the first sketch:

- Choose the printing process (SLA, FDM, SLS) based on the validation objective: fit, function, thermal, or mechanical performance.

- Orient the part to align primary load paths with the strongest directions of the chosen process - for example, avoiding critical loads perpendicular to the layer stack in FDM.

- Minimize overhangs that require supports and introduce self‑supporting angles where possible, typically above 45° relative to the build plane.

- Consolidate multi‑part assemblies into single printed units where feasible, integrating clips, hinges, and channels that would be expensive or impossible in traditional tooling.

The design output at this stage is not just geometry; it is a print‑ready model that anticipates manufacturing behavior rather than reacting to it after failure.

2. Afternoon: Slicing and Failure‑Mode Screening

Once geometry is frozen for the iteration, slicing software translates the model into machine instructions. At this point, the operator's job is less "press print" and more "risk assessment":

- Use layer previews to identify thin walls that may not properly form, unsupported bridges likely to sag, or abrupt cross‑section changes that can cause local warping.

- Simulate support placement and adjust orientation or minor geometry features to reduce support volume, particularly in SLA and FDM where supports drive both material consumption and labor.

- Confirm estimated build times align with the 24‑hour window, ensuring that print completion and post‑processing fit within the team's operating day.

A modest investment at this step - tens of minutes spent evaluating risk - avoids failed overnight jobs and protects the rhythm of the iteration cycle.

3. Evening to Overnight: Unattended Printing

With parameters locked, the job runs unattended. SLA and FDM systems may complete smaller parts in 2–6 hours, while SLS builds typically occupy an entire night including cool‑down. Modern machines monitor temperature, exposure, and basic error states automatically, reducing the need for constant supervision.

The critical management decision is batching:

- when time‑to‑first‑prototype is more important than utilization, single key parts may be prioritized;

- when a stable design is being prepared for multiple tests, fully packing the build volume becomes more economical.

Teams that explicitly choose between speed and utilization for each run gain better control over both cost and schedule.

4. Next Morning: Post‑Processing Without Bottlenecks

Post‑processing is where many "24‑hour" workflows actually fail. If cleaning, curing, depowdering, and finishing consume an entire workday, the advantage of overnight printing evaporates.

For SLA, automated wash units and UV curing stations can typically bring parts from green state to mechanically stable condition within a few hours, provided fixture loading and throughput match the printer's output. For SLS, automated depowdering, sieving, and optional surface finishing (such as bead blasting or vibratory smoothing) must be sized so that a full overnight build can be processed in the same morning.

Emerging in 2025–2026, digital thread integration is enabling teams to automatically capture build parameters, material batch data, and post‑processing conditions, creating a feedback loop that progressively refines design rules and predicts potential failures before printing begins. Similarly, multi‑material printing capabilities are expanding, allowing single builds to combine rigid and flexible materials or integrate conductive elements - capabilities that further accelerate functional validation cycles.

Critical bottleneck insight: Teams without post‑processing automation frequently see nominal 24‑hour cycles extend to 36-48 hours. Automated wash/cure stations for SLA and automated depowdering systems for SLS are increasingly essential infrastructure for reliably achieving true cycle times. This represents a key operational differentiator separating aspirational timelines from reproducible results.

The objective is not perfect cosmetic finishing on every iteration but predictable, repeatable steps that deliver functionally representative parts fast enough to support the next design decision.

5. Afternoon: Testing and Feedback Integration

Once the prototype is ready, the team immediately uses it to answer the question that triggered the iteration:

- Does the part assemble with mating components without interference or excess clearance?

- Do snap‑fits engage with the intended force and release without permanent deformation?

- Under representative thermal or mechanical loading, does the part behave in line with expected production material performance?

Quantitative feedback - measured displacement, force‑deflection curves, leakage rates - feeds directly into the CAD model the same day. Rather than treating prototypes as one‑off artifacts, the team treats each as a structured experiment whose results refine both geometry and assumptions.

.png)

Material Selection: Validating the Right Things

Choosing the wrong material can provide a fast but misleading answer. The goal is not to print "something that looks like the part," but "something that tells the truth about the part".

- For mechanical validation, SLS nylon and engineering‑grade SLA resins are appropriate because their tensile strength, modulus, and elongation can fall within a reasonable range of production thermoplastics when processed correctly.

- For high‑temperature or chemically aggressive environments, specialized high‑temperature resins or high‑performance polymers such as ULTEM or PEEK in compatible systems are necessary to avoid overestimating performance based on low‑temperature materials like PLA.

- For pure ergonomic and aesthetic checks - grip comfort, interface layout, screen visibility - lower‑cost materials and processes are acceptable, because the aim is spatial understanding rather than structural correlation.

A robust workflow explicitly distinguishes which properties are being validated in each iteration and selects materials accordingly, rather than defaulting to whatever filament or resin happens to be loaded.

Design for Additive Manufacturing as a Leverage Point

Printer specifications - speed, resolution, build volume - are easy to compare. The larger gains, however, often come from design decisions that work with the constraints of additive processes rather than against them.

Support and Orientation Strategy

In SLA and FDM, support structures consume material, extend build time, and create surfaces that require sanding or rework. By rotating parts, thickening or thinning local features, and introducing gentle tapers or fillets, designers can significantly cut support volume while maintaining functional geometry. Across multiple design iterations, these optimizations can reclaim days of schedule and substantial material cost.

Orientation is equally important mechanically. For FDM in particular, aligning principal stress directions parallel to the layer plane, rather than perpendicular to it, can markedly improve fatigue and ultimate strength without changing material or infill. Even in more isotropic processes like SLS, orientation affects residual stress, surface quality on critical faces, and dimensional accuracy for tight fits.

Assembly Consolidation

Traditional DFM for machining or molding encourages splitting complex functions into multiple parts to simplify tooling and assembly. DfAM often inverts this logic. With additive manufacturing, integrated channels, living hinges, lattice structures, and combined mounting features can be produced in a single build without additional tooling complexity.

By consolidating assemblies, teams can validate both functionality and assembly ergonomics in fewer iterations and with fewer potential error sources. Later, when designs transition toward injection molding, the insights from these integrated prototypes inform smarter part splits and more purposeful tooling decisions rather than arbitrary divisions.

Real‑World Impact Across Industries

Several industries already treat rapid additive prototyping as standard practice rather than an experiment:

Aerospace: Development teams have documented 65–75% reductions in prototype lead times for complex bracket assemblies, enabling multiple load‑path variants to be tested within a single traditional iteration window. This acceleration fundamentally changes the economics of design exploration.

Automotive: Manufacturers routinely print tools, gauges, and fixtures overnight to support production lines, turning formerly weeks‑long toolroom requests into next‑day improvements on the line.

Medical Device: Developers can significantly compress iteration cycles - for example, in an Xometry case study, a team completed 9 prototype iterations in just 20 days, compressing the time between design decision and clinically relevant testing data. This acceleration can support more efficient preparation for verification and validation phases in regulated designs.

These examples share a common pattern: teams do not merely acquire printers; they reorganize their development processes around short, disciplined iteration cycles.

When Rapid Prototyping Is Not the Right Tool

Despite its advantages, 3D printing is not always the correct answer. A 24‑hour cycle is most valuable when the primary constraints are learning speed and design risk, not per‑piece cost.

- For simple, high‑volume parts with stable requirements and tight unit‑cost targets, conventional tooling and molding remain more economical once the design is frozen.

- For regulatory‑driven products where every prototype must follow the same validated process as production, the value of ultra‑fast informal iterations may be limited to early concept exploration.

- For very large parts or those requiring materials not yet well supported by additive processes, the cost and complexity of printing can outweigh the learning gained.

The key is to use rapid prototyping where it changes decisions - not where it merely produces a more expensive version of an already obvious answer.

Implementation Considerations Beyond the Printer

Achieving reliable 24‑hour cycles requires more than a capable machine.

- Software integration between CAD, slicing, and printer management should minimize manual file handling and parameter re‑entry to avoid friction and mistakes.

- Material and consumable inventory must be managed so that print‑worthy ideas are not delayed by a lack of resin, powder, or wash capacity.

- Data capture - build parameters, orientation, material lots, post‑processing conditions - supports root‑cause analysis when parts fail unexpectedly and helps refine design rules over time. This systematic data collection is foundational to the digital thread workflows increasingly standard in 2026.

- Training is essential: engineers experienced in traditional DFM must learn to deliberately exploit additive freedoms (internal conduits, graded lattices, consolidation) while respecting new constraints (support, anisotropy, heat management).

Organizations that treat these aspects as a coherent system, rather than isolated tools, are the ones that reliably achieve genuine 24‑hour cycles instead of occasional lucky successes.

Speed as a Product Development Strategy

Rapid prototyping with 3D printing is not just about producing parts faster. It is about shifting product development from speculative planning to empirical learning at a pace that conventional methods cannot match. When teams can ask a concrete question in the morning and hold the physical answer the next day, risk becomes a manageable design variable instead of a deferred surprise.

For companies that design and engineer physical products, the competitive edge comes from coupling additive technologies with rigorous workflow discipline, clear validation objectives, and a culture that expects to learn from every iteration. The printer is only one component; the real advantage lies in how the organization designs, decides, and iterates around it.

If your current prototyping loop is still measured in weeks, not days, integrating a disciplined additive workflow with your DFM process is often the fastest lever to pull. This is precisely the gap we help close.

Rapid Prototyping Using 3D Printers: From Concept to Prototype in 24 Hours

Schedule an initial talk and get to know us better! You already have a basic brief? Send it over so we can have a more productive first meeting!

a meeting